It is stated that the period of a wave ranges from forty to sixty years, the cycles consist of alternating intervals of high sectoral growth and intervals of relatively slow growth.[3]

Long wave theory is not accepted by most academic economists.[4] Among economists who accept it, there is a lack of agreement about both the cause of the waves and the start and end years of particular waves. Among critics of the theory, the consensus is that it involves recognizing patterns that may not exist.

History of concept

The Soviet economist Nikolai Kondratiev (also written Kondratieff or Kondratyev) was the first to bring these observations to international attention in his book The Major Economic Cycles (1925) alongside other works written in the same decade.[5][6] In 1939, Joseph Schumpeter suggested naming the cycles “Kondratieff waves” in his honor. The underlying idea is closely linked to organic composition of capital.[citation needed]

Two Dutch economists, Jacob van Gelderen and Salomon de Wolff, had previously argued for the existence of 50- to 60-year cycles in 1913 and 1924, respectively.

Since the inception of the theory, various studies have expanded the range of possible cycles, finding longer or shorter cycles in the data. The Marxist scholar Ernest Mandel revived interest in long-wave theory with his 1964 essay predicting the end of the long boom after five years and in his Alfred Marshall lectures in 1979. However, in Mandel’s theory there are no long cycles, only distinct epochs of faster and slower growth spanning 20–25 years.[citation needed]

In 1996, George Modelski and William R. Thompson published a book documenting K-Waves dating back to 930 AD in China.[7] Separately, Michael Snyder wrote: “economic cycle theories have enabled some analysts to correctly predict the timing of recessions, stock market peaks and stock market crashes over the past couple of decades”.[8]

The historian Eric Hobsbawm also wrote of the theory: “That good predictions have proved possible on the basis of Kondratiev Long Waves—this is not very common in economics—has convinced many historians and even some economists that there is something in them, even if we don’t know what”.[9]

US-economist Anwar Shaikh analyses the movement of the general price level – prices expressed in gold – in the US and the UK since 1890 and identifies three long cycles with troughs ca. in 1895, 1939 and 1982. With this model 2018 was another trough between the third and a possible future fourth cycle.[10]

Characteristics of the cycle

Kondratiev identified three phases in the cycle, namely expansion, stagnation and recession. More common today is the division into four periods with a turning point (collapse) between expansion and stagnation.

Writing in the 1920s, Kondratiev proposed to apply the theory to the 19th century:

- 1790–1849, with a turning point in 1815.

- 1850–1896, with a turning point in 1873.

- Kondratiev supposed that in 1896 a new cycle had started.

The long cycle supposedly affects all sectors of an economy. Kondratiev focused on prices and interest rates, seeing the ascendant phase as characterized by an increase in prices and low interest rates while the other phase consists of a decrease in prices and high interest rates. Subsequent analysis concentrated on output.

Explanations of the cycle

Cause and effect

Understanding the cause and effect of Kondratiev waves is a useful academic discussion and tool. Kondratiev Waves present both causes and effects of common recurring events in capitalistic economies throughout history. Although Kondratiev himself made little differentiation between cause and effect, obvious points emerge intuitively.

The causes documented by Kondratiev waves, primarily include inequity, opportunity and social freedoms; although very often, much more discussion is made of the notable effects of these causes as well. Effects are both good and bad and include, to name just a few, technological advance, birthrates and revolutions/populism—and revolution’s contributing causes which can include racism, religious or political intolerance, failed-freedoms and opportunity, incarceration rates, terrorism and similar.

When inequity is low and opportunity is easily available, peaceful, moral decisions are preferred and Aristotle’s “Good Life” is possible (Americans call the good life “the American Dream“). Opportunity created the simple inspiration and genius for the Mayflower Compact for one example. Post-World War II and the 1850s post-California gold rush bonanza were times of great opportunity, low inequity and this resulted in unprecedented technological industrial advance too. Alternatively, when 1893’s global economic panics were not met with sufficient wealth-distributing government policies internationally, a dozen major revolutions resulted–perhaps also creating an effect we now call World War I.[11] Few would argue that World War II also began in response to failed attempts at creating economic opportunity-supporting government policy during the Great Depression of 1929 and the World War I’s Treaty of Versailles.

Technological innovation theory

According to the innovation theory, these waves arise from the bunching of basic innovations that launch technological revolutions that in turn create leading industrial or commercial sectors. Kondratiev’s ideas were taken up by Joseph Schumpeter in the 1930s. The theory hypothesized the existence of very long-run macroeconomic and price cycles, originally estimated to last 50–54 years.

In recent decades there has been considerable progress in historical economics and the history of technology, and numerous investigations of the relationship between technological innovation and economic cycles. Some of the works involving long cycle research and technology include Mensch (1979), Tylecote (1991), the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) (Marchetti, Ayres), Freeman and Louçã (2001), Andrey Korotayev[12] and Carlota Perez.

Perez (2002) places the phases on a logistic or S curve, with the following labels: the beginning of a technological era as irruption, the ascent as frenzy, the rapid build out as synergy and the completion as maturity.[13]

Demographic theory

Because people have fairly typical spending patterns through their life cycle, such as spending on schooling, marriage, first car purchase, first home purchase, upgrade home purchase, maximum earnings period, maximum retirement savings and retirement, demographic anomalies such as baby booms and busts exert a rather predictable influence on the economy over a long time period. The Easterlin hypothesis deals with the post-war baby-boom. Harry Dent has written extensively on demographics and economic cycles. Tylecote (1991) devoted a chapter to demographics and the long cycle.[14]

Land speculation

Georgists such as Mason Gaffney, Fred Foldvary and Fred Harrison argue that land speculation is the driving force behind the boom and bust cycle. Land is a finite resource which is necessary for all production and they claim that because exclusive usage rights are traded around, this creates speculative bubbles which can be exacerbated by overzealous borrowing and lending. As early as 1997, a number of Georgists predicted that the next crash would come in 2008.[15]

Debt deflation

Debt deflation is a theory of economic cycles which holds that recessions and depressions are due to the overall level of debt shrinking (deflating). Hence, the credit cycle is the cause of the economic cycle.

The theory was developed by Irving Fisher following the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression. Debt deflation was largely ignored in favor of the ideas of John Maynard Keynes in Keynesian economics, but it has enjoyed a resurgence of interest since the 1980s, both in mainstream economics and in the heterodox school of post-Keynesian economics and has subsequently been developed by such post-Keynesian economists as Hyman Minsky[16] and Steve Keen.[17]

Modern modifications of Kondratiev theory

Inequity appears to be the most obvious driver of Kondratiev waves, and yet some researches have presented a technological and credit cycle explanation as well.

There are several modern timing versions of the cycle although most are based on either of two causes: one on technology and the other on the credit cycle.

Additionally, there are several versions of the technological cycles and they are best interpreted using diffusion curves of leading industries. For example, railways only started in the 1830s, with steady growth for the next 45 years. It was after Bessemer steel was introduced that railroads had their highest growth rates. However, this period is usually labeled the age of steel. Measured by value added, the leading industry in the U.S. from 1880 to 1920 was machinery, followed by iron and steel.[18]

Any influence of technology during the cycle that began in the Industrial Revolution pertains mainly to England. The U.S. was a commodity producer and was more influenced by agricultural commodity prices. There was a commodity price cycle based on increasing consumption causing tight supplies and rising prices. That allowed new land to the west to be purchased and after four or five years to be cleared and be in production, driving down prices and causing a depression as in 1819 and 1839.[19] By the 1850s, the U.S. was becoming industrialized.[20]

The technological cycles can be labeled as follows:

- Industrial Revolution (1771)

- Age of Steam and Railways (1829)

- Age of Steel and Heavy Engineering (1875)

- Age of Oil, Electricity, the Automobile and Mass Production (1908)

- Age of Information and Telecommunications (1971)

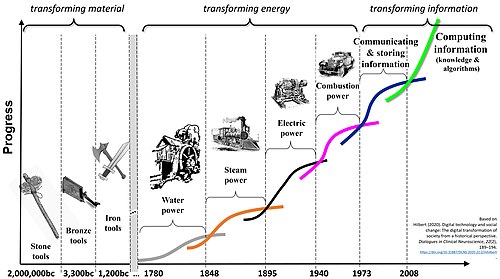

Some argue that this logic can be extended. The custom of classifying periods of human development by its dominating general purpose technology has surely been borrowed from historians, starting with the Stone Age. Including those, authors distinguish three different long-term metaparadigms, each with different long waves. The first focused on the transformation of material, including stone, bronze, and iron. The second, often referred to as industrial revolutions, was dedicated to the transformation of energy, including water, steam, electric, and [[internal combustion engine|combustion power]. Finally, the most recent metaparadigm aims at transforming information. It started out with the proliferation of communication and stored data and has now entered the age of algorithms, which aims at creating automated processes to convert the existing information into actionable knowledge.[21]

Several papers on the relationship between technology and the economy were written by researchers at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA). A concise version of Kondratiev cycles can be found in the work of Robert Ayres (1989) in which he gives a historical overview of the relationships of the most significant technologies.[22] Cesare Marchetti published on Kondretiev waves and on the diffusion of innovations.[23][24] Arnulf Grübler’s book (1990) gives a detailed account of the diffusion of infrastructures including canals, railroads, highways and airlines, with findings that the principal infrastructures have midpoints spaced in time corresponding to 55-year K wavelengths, with railroads and highways taking almost a century to complete. Grübler devotes a chapter to the long economic wave.[25] In 1996, Giancarlo Pallavicini published the ratio between the long Kondratiev wave and information technology and communication.[26]

Korotayev et al. recently employed spectral analysis and claimed that it confirmed the presence of Kondratiev waves in the world GDP dynamics at an acceptable level of statistical significance.[3][27] Korotayev et al. also detected shorter business cycles, dating the Kuznets to about 17 years and calling it the third harmonic of the Kondratiev, meaning that there are three Kuznets cycles per Kondratiev.

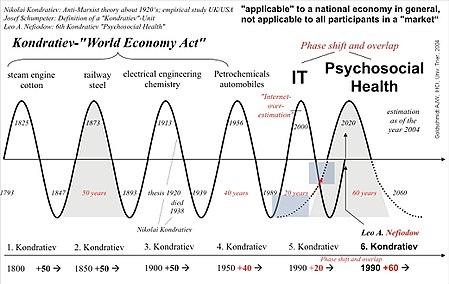

Leo A. Nefiodow shows that the fifth Kondratieff ended with the global economic crisis of 2000–2003 while the new, sixth Kondratieff started simultaneously.[28] According to Leo A. Nefiodow, the carrier of this new long cycle will be health in a holistic sense—including its physical, psychological, mental, social, ecological and spiritual aspects; the basic innovations of the sixth Kondratieff are “psychosocial health” and “biotechnology”.[29]

More recently, the physicist and systems scientist Tessaleno Devezas advanced a causal model for the long wave phenomenon based on a generation-learning model[30] and a nonlinear dynamic behaviour of information systems.[31] In both works, a complete theory is presented containing not only the explanation for the existence of K-Waves, but also and for the first time an explanation for the timing of a K-Wave (≈60 years = two generations).

A specific modification of the theory of Kondratieff cycles was developed by Daniel Šmihula. Šmihula identified six long-waves within modern society and the capitalist economy, each of which was initiated by a specific technological revolution:[32]

- 1. Wave of the Financial-agricultural revolution (1600–1780)

- 2. Wave of the Industrial revolution (1780–1880)

- 3. Wave of the Technical revolution (1880–1940)

- 4. Wave of the Scientific-technical revolution (1940–1985)

- 5. Wave of the Information and telecommunications revolution (1985–2015)

- 6. Hypothetical wave of the post-informational technological revolution (Internet of things/renewable energy transition?) (2015–2035?)

Unlike Kondratieff and Schumpeter, Šmihula believed that each new cycle is shorter than its predecessor. His main stress is put on technological progress and new technologies as decisive factors of any long-time economic development. Each of these waves has its innovation phase which is described as a technological revolution and an application phase in which the number of revolutionary innovations falls and attention focuses on exploiting and extending existing innovations. As soon as an innovation or a series of innovations becomes available, it becomes more efficient to invest in its adoption, extension and use than in creating new innovations. Each wave of technological innovations can be characterized by the area in which the most revolutionary changes took place (“leading sectors”).

Every wave of innovations lasts approximately until the profits from the new innovation or sector fall to the level of other, older, more traditional sectors. It is a situation when the new technology, which originally increased a capacity to utilize new sources from nature, reached its limits and it is not possible to overcome this limit without an application of another new technology.

For the end of an application phase of any wave there are typical an economic crisis and economic stagnation. The financial crisis of 2007–2008 is a result of the coming end of the “wave of the Information and telecommunications technological revolution”. Some authors have started to predict what the sixth wave might be, such as James Bradfield Moody and Bianca Nogrady who forecast that it will be driven by resource efficiency and clean technology.[33] On the other hand, Šmihula himself considers the waves of technological innovations during the modern age (after 1600 AD) only as a part of a much longer “chain” of technological revolutions going back to the pre-modern era.[34] It means he believes that we can find long economic cycles (analogical to Kondratiev cycles in modern economy) dependent on technological revolutions even in the Middle Ages and the Ancient era.

Criticism of long cycles

Long wave theory is not accepted by many academic economists. However, is important for innovation-based, development and evolutionary economics. Yet, among economists who accept it there has been no formal universal agreement about the standards that should be used universally to place start and the end years for each wave. Agreement of start and end years can be +1 to 3 years for each 40- to 65-year cycle.

Health economist and biostatistician Andreas J. W. Goldschmidt searched for patterns and proposed that there is a phase shift and overlap of the so-called Kondratiev cycles of IT and health (shown in the figure). He argued that historical growth phases in combination with key technologies does not necessarily imply the existence of regular cycles in general. Goldschmidt is of the opinion that different fundamental innovations and their economic stimuli do not exclude each other as they mostly vary in length and their benefit is not applicable to all participants in a market.[35]

Joseph Schumpeter, a professor at Harvard University, was among the key advocates of the existence of Kondratiev wave.